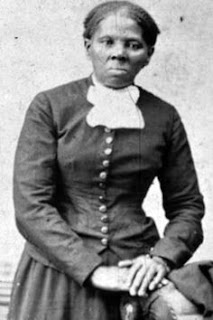

Harriet Tubman, first African-American to appear on U.S. paper currency and first woman in more than a century

Harriet Tubman escaped slavery to become a leading abolitionist. She led hundreds of enslaved people to freedom along the route of the Underground Railroad.

Synopsis

Harriet Tubman was an American bondwoman who escaped from slavery in the South to become a leading abolitionist before the American Civil War. She was born in Maryland in 1820, and successfully escaped in 1849. Yet she returned many times to rescue both family members and non-relatives from the plantation system. She led hundreds to freedom in the North as the most famous "conductor" on the Underground Railroad, an elaborate secret network of safe houses organized for that purpose.

Early Life

Harriet Tubman was born to enslaved parents in Dorchester County, Maryland, and originally named Araminta Harriet Ross. Her mother, Harriet “Rit” Green, was owned by Mary Pattison Brodess. Her father, Ben Ross, was owned by Anthony Thompson, who eventually married Mary Brodess. Araminta, or “Minty,” was one of nine children born to Rit and Ben between 1808 and 1832. While the year of Araminta’s birth is unknown, it probably occurred between 1820 and 1825.

Minty’s early life was full of hardship. Mary Brodess’ son Edward sold three of her sisters to distant plantations, severing the family. When a trader from Georgia approached Brodess about buying Rit’s youngest son, Moses, Rit successfully resisted the further fracturing of her family, setting a powerful example for her young daughter.

Physical violence was a part of daily life for Tubman and her family. The violence she suffered early in life caused permanent physical injuries. Harriet later recounted a particular day when she was lashed five times before breakfast. She carried the scars for the rest of her life. The most severe injury occurred when Tubman was an adolescent. Sent to a dry-goods store for supplies, she encountered a slave who had left the fields without permission. The man’s overseer demanded that Tubman help restrain the runaway. When Harriet refused, the overseer threw a two-pound weight that struck her in the head. Tubman endured seizures, severe headaches and narcoleptic episodes for the rest of her life. She also experienced intense dream states, which she classified as religious experiences.

The line between freedom and slavery was hazy for Tubman and her family. Harriet Tubman’s father, Ben, was freed from slavery at the age of 45, as stipulated in the will of a previous owner. Nonetheless, Ben had few options but to continue working as a timber estimator and foreman for his former owners. Although similar manumission stipulations applied to Rit and her children, the individuals who owned the family chose not to free them. Despite his free status, Ben had little power to challenge their decision.

By the time Harriet reached adulthood, around half of the African-American people on the eastern shore of Maryland were free. It was not unusual for a family to include both free and enslaved people, as did Tubman’s immediate family. In 1844, Harriet married a free black man named John Tubman. Little is known about John Tubman or his marriage to Harriet. Any children they might have had would have been considered enslaved, since the mother’s status dictated that of any offspring. Araminta changed her name to Harriet around the time of her marriage, possibly to honor her mother.

Escape from Slavery and Abolitionism

Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery in 1849, fleeing to Philadelphia. Tubman decided to escape following a bout of illness and the death of her owner in 1849. Tubman feared that her family would be further severed, and feared for own her fate as a sickly slave of low economic value. She initially left Maryland with two of her brothers, Ben and Henry, on September 17, 1849. A notice published in the Cambridge Democrat offered a $300 reward for the return of Araminta (Minty), Harry and Ben. Once they had left, Tubman’s brothers had second thoughts and returned to the plantation. Harriet had no plans to remain in bondage. Seeing her brothers safely home, she soon set off alone for Pennsylvania.

Tubman made use of the network known as the Underground Railroad to travel nearly 90 miles to Philadelphia. She crossed into the free state of Pennsylvania with a feeling of relief and awe, and recalled later: “When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.”

Rather than remaining in the safety of the North, Tubman made it her mission to rescue her family and others living in slavery. In December 1850, Tubman received a warning that her niece Kessiah was going to be sold, along with her two young children. Kessiah’s husband, a free black man named John Bowley, made the winning bid for his wife at an auction in Baltimore. Harriet then helped the entire family make the journey to Philadelphia. This was the first of many trips by Tubman, who earned the nickname “Moses” for her leadership. Over time, she was able to guide her parents, several siblings and about 60 others to freedom. One family member who declined to make the journey was Harriet’s husband, John, who preferred to stay in Maryland with his new wife.

The dynamics of escaping slavery changed in 1850, with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law. This law stated that escaped slaves could be captured in the North and returned to slavery, leading to the abduction of former slaves and free blacks living in Free States. Law enforcement officials in the North were compelled to aid in the capture of slaves, regardless of their personal principles. In response to the law, Tubman re-routed the Underground Railroad to Canada, which prohibited slavery categorically.

In December 1851, Tubman guided a group of 11 fugitives northward. There is evidence to suggest that the party stopped at the home of abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass.

In April 1858, Tubman was introduced to the abolitionist John Brown, who advocated the use of violence to disrupt and destroy the institution of slavery. Tubman shared Brown’s goals and at least tolerated his methods. Tubman claimed to have had a prophetic vision of Brown before they met. When Brown began recruiting supporters for an attack on slaveholders at Harper’s Ferry, he turned to “General Tubman” for help. After Brown’s subsequent execution, Tubman praised him as a martyr.

Harriet Tubman remained active during the Civil War. Working for the Union Army as a cook and nurse, Tubman quickly became an armed scout and spy. The first woman to lead an armed expedition in the war, she guided the Combahee River Raid, which liberated more than 700 slaves in South Carolina.

Later Life

In early 1859, abolitionist Senator William H. Seward sold Tubman a small piece of land on the outskirts of Auburn, New York. The land in Auburn became a haven for Tubman’s family and friends. Tubman spent the years following the war on this property, tending to her family and others who had taken up residence there. In 1869, she married a Civil War veteran named Nelson Davis. In 1874, Harriet and Nelson adopted a baby girl named Gertie.

Despite Harriet’s fame and reputation, she was never financially secure. Tubman’s friends and supporters were able to raise some funds to support her. One admirer, Sarah H. Bradford, wrote a biography entitled Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, with the proceeds going to Tubman and her family. Harriet continued to give freely in spite of her economic woes. In 1903, she donated a parcel of her land to the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Auburn. The Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged opened on this site in 1908.

As Tubman aged, the head injuries sustained early in her life became more painful and disruptive. She underwent brain surgery at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital to alleviate the pains and "buzzing" she experienced regularly. Tubman was eventually admitted into the rest home named in her honor. Surrounded by friends and family members, Harriet Tubman died of pneumonia in 1913.

Harriet Tubman, widely known and well-respected while she was alive, became an American icon in the years after she died. A survey at the end of the 20th century named her as one of the most famous civilians in American history before the Civil War, third only to Betsy Ross and Paul Revere. She continues to inspire generations of Americans struggling for civil rights with her bravery and bold action.

When she died, Tubman was buried with military honors at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn. The city commemorated her life with a plaque on the courthouse. Tubman was celebrated in many other ways throughout the nation in the 20th century. Dozens of schools were named in her honor, and both the Harriet Tubman Home in Auburn and the Harriet Tubman Museum in Cambridge serve as monuments to her life.

Harriet Tubman on the $20 Bill

In April 2016, the U.S. Treasury Department announced that Harriet Tubman will replace Andrew Jackson on the center of a new $20 bill. The announcement came after the Treasury Department received a groundswell of public comments, following Women on 20s’ campaign calling for a notable American woman to appear on U.S. currency. “Secretary Lew’s choice of the freed slave and freedom fighter Harriet Tubman to one day feature on the $20 note is an exciting one, especially given that she emerged as the choice of more than half a million voters in our online poll last Spring,” Women on 20s stated on its website. “Not only did she devote her life to racial equality, she fought for women’s rights alongside the nation’s leading suffragists.”

Credit: Bio.

Comments

Post a Comment

Be sociable, share your opinion!

Post a Comment :)